Medical College Admission Test: Verbal Reasoning, Biological Sciences, Physical Sciences, Writing Sample: MCAT-TEST

Want to pass your Medical College Admission Test: Verbal Reasoning, Biological Sciences, Physical Sciences, Writing Sample MCAT-TEST exam in the very first attempt? Try Pass2lead! It is equally effective for both starters and IT professionals.

- Vendor: MCAT

- Exam Code: MCAT-TEST

- Exam Name: Medical College Admission Test: Verbal Reasoning, Biological Sciences, Physical Sciences, Writing Sample

- Certifications: MCAT Certifications

- Total Questions: 812 Q&As

- Updated on: Dec 15, 2024

- Note: Product instant download. Please sign in and click My account to download your product.

- Q&As Identical to the VCE Product

- Windows, Mac, Linux, Mobile Phone

- Printable PDF without Watermark

- Instant Download Access

- Download Free PDF Demo

- Includes 365 Days of Free Updates

VCE

- Q&As Identical to the PDF Product

- Windows Only

- Simulates a Real Exam Environment

- Review Test History and Performance

- Instant Download Access

- Includes 365 Days of Free Updates

Passing Certification Exams Made Easy

Everything you need prepare and quickly pass the tough certification exams the first time

- 99.5% pass rate

- 7 Years experience

- 7000+ IT Exam Q&As

- 70000+ satisfied customers

- 365 days Free Update

- 3 days of preparation before your test

- 100% Safe shopping experience

- 24/7 Support

MCAT MCAT-TEST Last Month Results

Free MCAT-TEST Exam Questions in PDF Format

Related MCAT Certifications Exams

MCAT-TEST Online Practice Questions and Answers

Questions 1

Our sense of smell is arguably the most powerful of our five senses, but it also the most elusive. It plays a vital yet mysterious role in our lives. Olfaction is rooted in the same part of the brain that regulates such essential functions as body metabolism, reaction to stress, and appetite. But smell relates to more than physiological function: its sensations are intimately tied to memory, emotion, and sexual desire. Smell seems to lie somewhere beyond the realm of conscious thought, where, intertwined with emotion and experience, it shapes both our conscious and unconscious lives.

The peculiar intimacy of this sense may be related to certain anatomical features. Smell reaches the brain more directly than do sensations of touch, sight, or sound. When we inhale a particular odor, air containing volatile odiferous molecules is warmed and humidified as it flows over specialized bones in the nose called turbinates. As odor molecules land on the olfactory nerves, these nerves fire a message to the brain. Thus olfactory neurons render a direct path between the stimulus provided by the outside environment and the brain, allowing us to rapidly perceive odors ranging from alluring fragrances to noisome fumes.

Certain scents, such as jasmine, are almost universally appealing, while others, like hydrogen sulfide (which emits a stench reminiscent of rotten eggs), are usually considered repellent, but most odors evoke different reactions from person to person, sometimes triggering strong emotional states or resurrecting seemingly forgotten memories. Scientists surmise that the reason why we have highly personal associations with smells is related to the proximity of the olfactory and emotional centers of our brain. Although the precise connection between emotion and olfaction remains a mystery, it is clear that emotion, memory, and smell are all rooted in a part of the brain called the limbic lobe.

Even though we are not always conscious of the presence of odors, and are often unable to either articulate or remember their unique characteristics, our brains always register their existence. In fact, such a large amount of human brain tissue is devoted to smell that scientists surmise the role of this sense must be profound. Moreover, neurobiological research suggests that smell must have an important function because olfactory neurons can regenerate themselves, unlike most other nerve cells. The importance of this sense is further supported by the fact that animals experimentally denied the olfactory sense do not develop full and normal brain function.

The significance of olfaction is much clearer in animals than in human beings. Animal behavior is strongly influenced by pheromones, which are odors that induce psychological or behavioral changes and often provide a means of communicating within a species. These chemical messages, often a complex blend of compounds, are of vital importance to the insect world. Honeybees, for example, organize their societies through odor: the queen bee exudes an odor that both inhibits worker bees from laying eggs and draws drones to her when she is ready to mate. Mammals are also guided by their sense of smell. Through odors emitted by urine and scent glands, many animals maintain their territories, identify one another, signal alarm, and attract mates.

Although our olfactory acuity can't rival that of other animal species, human beings are also guided by smell. Before the advent of sophisticated laboratory techniques, physicians depended on their noses to help diagnose illness. A century ago, it was common medical knowledge that certain bacterial infections carry the musty odor of wine, that typhoid smells like baking bread, and that yellow fever smells like meat. While medical science has moved away from such subjective diagnostic methods, in everyday life we continue to rely on our sense of small, knowingly or not, to guide us.

The author describes the sense of smell as elusive because:

A. odiferous molecules are extremely volatile.

B. the functions of smell are emotional rather than physiological.

C. the function and effects of smell are not fully understood.

D. olfactory sensations are more fleeting than those of other senses.

Questions 2

The mind, just like the body, has its needs. The needs of the body are the foundations of society; those of the mind are its amenities. While government and laws provide for the safety and well-being of men when they gather together, the sciences and the arts, which are less despotic but perhaps more powerful, spread garlands of flowers over the iron chains that bind them, stifle in them the sense for that original liberty for which they seem to have been born, cause them to love their own enslavement, and turn them into so-called "civilized people." Necessity raised thrones; the sciences and the arts have strengthened them. O earthly powers: cherish talents and protect those who cultivate them. O civilized people, cultivate them: you happy slaves owe to them that delicate and refined taste of which you are so proud, that gentleness of character and urbanity of manner which make relations among you so amiable and easy -- in other words, that semblance of all the virtues, none of which you actually possess... ...How pleasant it would be to live among us, if our external appearance were always a reflection of what is in our hearts, if decency were virtue, if our maxims served as our rules, and if true philosophy were inseparable from the title of philosopher! But so many qualities are seldom found together, and virtue hardly ever walks in such great pomp. Richness of adornment may be the mark of a man of taste, but a healthy, robust man is known by other signs: it is beneath the rustic clothes of a farmer, and not the gilt of a courtier, that strength and vigor of the body will be found. Ornamentation is just as foreign to virtue, which is the strength and vigor of the soul. The good man is an athlete who prefers to compete in the nude: he disdains all those vile ornaments which would hinder the use of his strength, ornaments which were for the most part invented only to hide some deformity. Before art had molded our manners and taught our passions to speak an affected language, our customs were rustic but natural, and differences in conduct revealed clearly differences in character. Human nature, basically, was no better, but men found security in being able to see through each other easily, and this advantage, which we no longer appreciate, spared them many vices. Now that more subtle refinements and more delicate taste have reduced the art of pleasing to set rules, a base and deceptive uniformity prevails in our behavior, and all minds seem to have been cast in the same mold. Incessantly politeness and propriety make demands on us, and incessantly we follow usage but never our own inclinations. We no longer dare to appear as we are, and under this perpetual constraint, the men who form this herd called society, when placed in the same circumstances, will all act similarly unless stronger motives direct them to do otherwise. Therefore we will never know well those with whom we deal, for to know our friends we will have to wait for some crises to arise -- which is to say that we will have to wait until it is too late, as it is for these very crises that it is essential to know one's friends well. What vice would not accompany this uncertainty? No more sincere friendships, no more genuine esteem, no more well-based confidence. Suspicion, offenses, fears, coldness, reserve, hatred and betrayal will constantly hide under the same false veil of politeness, under that much touted urbanity which we owe to the enlightenment of our times. The name of the Master of the Universe will no longer be profaned by swearing, but insulted by blasphemies that will not offend our scrupulous ears. Men will not boast of their own merits, but belittle those of others. An enemy will not be crudely insulted, but adroitly slandered. National hatreds will die, but so will patriotism. A dangerous skepticism will take the place of the scorning of ignorance. Some excesses will be forbidden, some vices dishonored, but others will be dignified with the name of virtues, and one must either have them or feign them. Let those who want to praise the sobriety of the sages of our time do so; as for me, I see in it only a refinement of intemperance that is as unworthy of my praise as their hypocritical simplicity.

Based on the opinions professed in the passage, the author would most likely believe that "well-based confidence" (line 59) would most likely arise from:

A. the uncertainty of not knowing another's true feelings.

B. knowledge of the true content of another's character.

C. the parity between appearance and true virtue.

D. knowledge of the absence of truth in the "veil" of politeness.

Questions 3

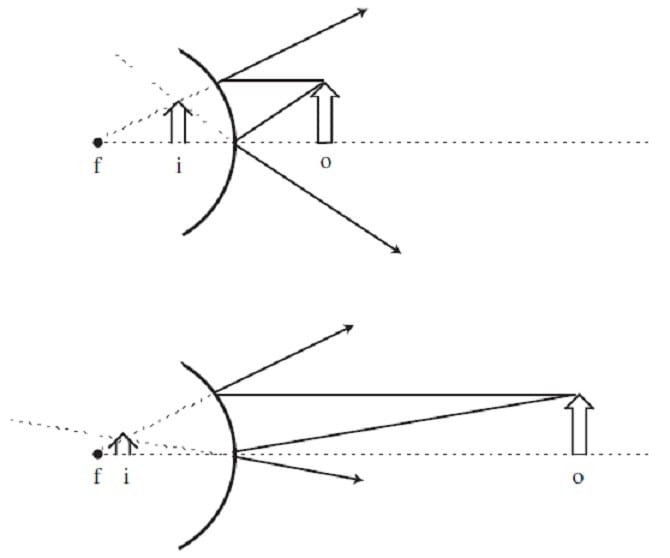

Aclown stands with her toes touching a fun house mirror with a convex bottom and a concave top. Which of the following best describes the distortion of the clown's image as she walks away from the mirror?

A. Her head will shrink; her feet will grow, then shrink.

B. Her head will shrink then grow; her feet will shrink, then grow.

C. Her head will grow; her feet will grow.

D. Her head will grow, then shrink; her feet will shrink.

Reviews

-

A valid dumps. It helped me pass the exam in short time. Thanks a million.

-

Wonderful study material. I used this material only half a month, and eventually I passed the exam with high score. The answers are accurate and detailed. You can trust on it.

-

Valid dumps. Thanks very much.

-

Test engine works fine. Pass my exam. Thank you.

-

took the exams yesterday and scored 9xx.dumps are valid. almost all of the multiple choice came out. I advice know ur material very well and then U can read dumps. good success

-

Very good study material, I just passed my exam with the help of it. Good luck to you.

-

Valid study material! Go get it now!!!

-

The Dumb is valid 100%.100%

-

There are so many new questions in the latest update. You can trust on this. Good luck to you all, guys.

-

Simulation still valid..passed with a score of 917 :-D

Printable PDF

Printable PDF